For beginners and teachers

So much more goes into a great scene than meets the eye. Scene development is a fine science, if not an exact one.

If you’re a beginning screenwriter, everything feels a bit foreign. Especially at first. But a scene is a scene, right? Put them together and you have a script. Well… Maybe not.

You’re already a storyteller. Maybe you’re a novel or short story writer. But screenwriting isn’t quite like any other writing you’ve done to date.

Even the language we use is unique to the craft.

Come on, you say. It can’t be that different. Right? A story is a story, after all. And writing is writing.

Or is writing just writing?

And of course, you know that some scenes, especially opening and closing scenes are super important and therefore take time and attention to craft.

But the ones in between? They can’t be that important. As long as my characters go through their arcs and the story gets told, the individual scenes aside from those memorable ones are not so significant, right?

Yes, and… well, not really.

Screenplays differ from novels in numerous ways. (I’ll itemize the differences in another blog, but for now, just take my word for it.)

One of the ways screenplays are unique is that scenes differ from chapters, which are different from acts, but they also share similarities. Neither novel nor short story is limited by time. Your short story comes close, but not in the same way.

When writing a screenplay scene, you need to be aware of many things, including what happened before, what’s coming next, and whether you start the current scene on a positive note and end neutral; or start on a negative and end positively.

Wait. What does that mean?

Scenes to a movie are like sentences to a paragraph. And paragraphs to a chapter. Or even words to a sentence. Some are short and snappy. Others might turn into memes or catchphrases or send the reader scrambling for a dictionary. Others are simple, but slow and lingering and bring you deeper into the subject so you truly feel it.

When a reader makes a comment about your scene pacing, it’s like saying you need to get a grasp on syntax.

Like anything well written, a screenplay should carry a reader into a world they don’t want leave and are willing to suspend their disbelief, even on the page.

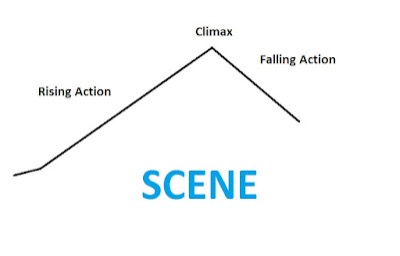

You need to construct your scenes so they change. They have a different mood when they start than when they end. Watch any of your favorite shows or movies and you’ll notice this immediately. A scene that ends the way it starts serves no purpose to move the story forward and hangs like an awkward conversation.

There are people in this world who are natural-born storytellers. They do this like they breathe. Without effort. With barely a thought. Most of the rest of us have to work at the structure.

Get in late, get out early

When we watch a show, or walk into a room, we can pretty quickly piece together what happened before we got there.

That’s what it means to get in late to a scene. Start in the middle of a conversation or an action event. Don’t waste any time setting it up. Give your audience credit for intelligence enough to fill the gaps.

Same thing when you exit. Keep your pace brisk by getting out early. Again, giving your audience, in this case your reader, the benefit of the doubt. They know what’s coming if it’s ordinary. Or, they’ll appreciate it if you mask something interesting you intend to reveal later.

It helps when you approach your scenes with a plan. Here’s where you can really get some help with our Scene Accelerator guide and its companion Scene Sequencer™.

It’s so useful to see at a glance and work out what has to happen before and after your scene. It also prompts you to test the scene’s arc, identify the critical info you plan to reveal in this scene, as well as the scene’s purpose in the story.

Your scenes also need structure

The Scene Accelerator is useful to all writers, including those starting out. But also to aspiring screenwriters who work to hone their craft even more. This guide and the whole toolkit appeal to writers who love structure and tools. And to those who crave it for its ability to tame the wildest imagination, but find it challenging.

Some writers keep their outlines in their heads or on notepads. Most of us benefit from being able to see the outline in front of us, either as a graphic or a chart, or using index cards. But every writer outlines in some way, even if it’s just scribbles on a legal pad.

I’m sure there will be a handful who claim they don’t, but unless you’re being dictated to by an unseen muse, I think you’ll agree you do some sketching and planning, even if you don’t use a beat board or beat sheet.

If there is no change in the scene, delete it or fix it. If the scene is full of color and emotional change, but doesn’t further the story, take it out, no matter how it hurts.

I’m not suggesting you delete the great scene that doesn’t quite fit. Of course not. No self-respecting writer would delete anything they loved. But do put it on a shelf. If you do it consciously, its true story might present itself. Or you could turn it into a short. Just don’t try to shove it into your narrative feature in progress.

Memorable classic scenes

Let’s go back to those memorable scenes. Think about them. They are magnificent. Like the bedroom / horse scene in The Godfather. Or the ‘We’re gonna need a bigger boat’ scene in Jaws. And the rabbit soup scene in Fatal Attraction.

How about the “My name is Iñigo Montoya” sword fighting scene with the six-fingered man in The Princess Bride? Or the razor scene in The Color Purple? “My sister, my daughter,” in Chinatown? Play it, Sam, from Casablanca?

Not one of those scenes is remotely forgettable. Anyone who saw those films cannot “unremember” those scenes. It’s like not imagining a Pink Panther on a bicycle being chased by a pack of dogs in Central Park.

But what do they have in common?

Think about it.

Those scenes define the word ‘memorable.’ They are etched in the memories of moviegoers worldwide. And they are often quoted or parodied.

Tools Help

If you want some help, the Badass Scene Accelerator™ guide helps you chart the bits of the script you know are necessary materials in their construction.

This isn’t a personal preference by the way. It’s part of the science of storytelling. We know it when we’re in the zone and the words write themselves. You can feel the inner parts

See what screenwriting instructor September Fawkes says about pacing at the scene level.

Scenes work best where they live

What does that mean? While those great scenes can be seen and appreciated, even if you’ve never seen the film, not one of them actually stands alone. The reason they are truly memorable is because of where they fall in a well-constructed script.

A memorable scene is perfect in itself, but also perfectly placed in the story. It appears at a particular moment when the audience’s emotions have been molded and manipulated to be just so. When viewed in their proper context, those memorable scenes are brilliant.

They might appear to do so at first blush, and in fact they are that powerful in their own right that they could be used as a preview, if you don’t mind spoiler trailers. But the nuances, the depth of character, the

I realize, of course, that these references are from last century, but those scenes remain classic in films still worthy of study by every aspiring screenwriter.

The point is, even though the scene itself is glorious and memorable, it is even more so when seen in the context it was intended. Meaning the setup was present and clever, the previous and subsequent scenes are equally well-defined and planned. And the whole thing sings like a well-practiced choir.

Want more fresh tips and advice on screenwriting? Sign up for alerts. We’ll send you occasional emails to let you know when we publish new content.