The concept of “show, don’t tell” is one of the more difficult maxims for new screenwriters to wrap their heads around. Especially if they come from the novel or short story writing world.

And it’s super important to learn and practice when you’re writing for the screen.

In fact, I would argue the discipline you learn when “showing, not telling” in your screenplays will easily migrate to your other writing and will make it come alive in a new way.

And there’s a scientific reason for why showing works better than telling. See what Michael has learned in his article on the brain’s Limbic System.

Note that here we’re not talking about exposition. That’s a whole other topic and we’ll get to that in another blog post. The expression “show, don’t tell” means writing in visual language so the reader can infer the character’s emotions from their actions.

When I sent my early screenplays for notes, it seemed the readers all drew from the same catch-phrase book, designed to be both helpful and encouraging.

“Remember that film is a visual medium.”

Duh, I thought, again and again. Then remembered my go-to ‘clue from the universe’ edict that if I heard something twice, from two different sources, I’d better start listening.

So I started to become aware of every sentence in my action lines. Am I showing? Is this telling?

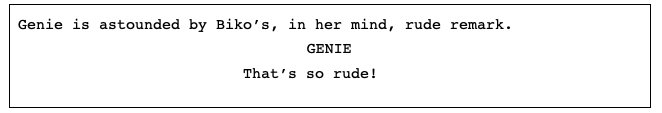

For example, I knew it wasn’t correct to write: Genie is astounded by Biko’s rudeness. And this below definitely doesn’t work.

For one, I try (and you should too) to never use ‘is’ in my screenplays because it indicates substandard writing, either passive voice, like in the example is astounded by, or preludes another no-no, a present participle like walking.

Think like a camera

But more importantly, the golden ticket to understanding how to show, not tell is to think like a camera. Think of every action line as a camera shot. Don’t write the shots, that’s not your job at the early stage of a script. But imagine what the camera sees. If the camera can’t see it, delete it.

In the example action line above, the only thing the camera can see is Genie. It can’t see into her mind. It can’t know about an earlier remark by another character, and it doesn’t know what astounded looks like.

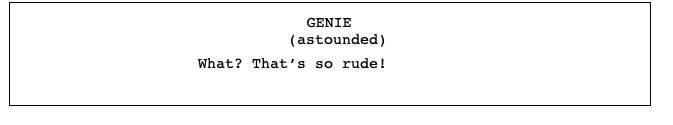

So, how can I convey Genie’s astonishment? She’s been told by her Uber driver to get out into the pouring rain. I have to describe her reaction. Some writers rely on what actors call ‘wrylies’ by putting emotions in parentheticals above dialogue.

But that still doesn’t work. We’ve already established that the camera has no idea what astounded looks like. What does it look like? Is that even the right word? Instead of telling or thought words, which work fine in novels, as screenwriters we need to show the emotions through the character’s actions.

This is tricky, because we also have to avoid too much ‘directing on the page’ – but that’s for another discussion. For the moment, let’s see how we can show the reader Genie’s reaction. Turns out, astounded doesn’t remotely cover it.

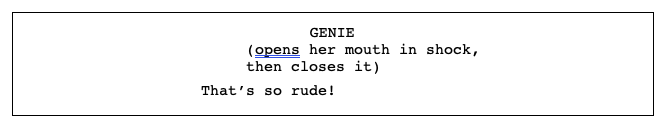

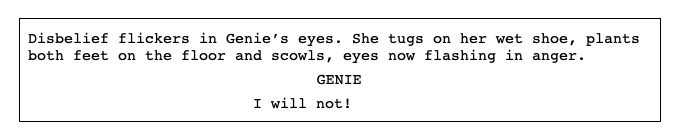

Okay, here’s a stab at changing the parenthetical.

So, that definitely shows a reaction. But it’s not a great way to do it. I’ve seen entire screenplays written with long parentheticals like this. Too many “directorial” parentheticals are super distracting and become a writer’s crutch to avoid action lines. Also, they should never spill onto a second line.

You’ve already learned the basic parts of a screenplay: Scene headings, action lines, and dialogue. Parentheticals are NOT a basic part of a screenplay. They’re just a tool.

You’re free to use them, of course. But don’t depend on them to convey emotions. Why? Because a) they’re rarely effective, and b) actors and readers both dislike them, for different reasons. Actors, because they’d prefer to interpret the script and the character than be ‘instructed’ by a writer. And readers, because when used excessively they interrupt the flow and yank the reader from the story.

Parentheticals work best when they show the character moving. Or if they change the person they’re speaking to mid-dialogue.

Back to showing Genie’s response to perceived rudeness, the previous attempts of which were kind of ‘on the nose.’ But that’s another discussion.

Once I start concentrating on showing, her dialogue from earlier sounds off. In fact, I’m going to leave it to the actors to demonstrate whether Biko is rude or not.

What I do know is that my main character, Genie, is not a happy panda; and yes, she reacted to what she perceives as rudeness by Biko. But by showing her reaction, I can completely ditch the word ‘rude’ from her dialogue. Why? Because it’s already obvious. In screenwriting, we don’t write what the reader (or we hope, eventually the viewer) can perceive without words.

It’s a tricky tightrope walk, this business of showing without telling. We’re writing to first please the readers, who are reading while thinking about what the producers, directors, and actors will think. And overall, we want absolutely nothing to bump the reader from the story for an instant.

You be the judge. Is that telling? Or showing?